Media unionism and the birth of the NUJP

by Joel C. Paredes

MANILA — During the dark days of Martial Law, our late colleague Antonio Ma. Nieva was considered “dangerous” — and a “communist” — among the ranks of the conservative Philippine press. Together with a handful of working journalists, he challenged the media institutions as “instruments of political repression” in the country.

As he put it: “In the Marcos years, the controlled media wrote reams of copy in praise of the regime, justifying ‘salvaging,’ the militarization of the countryside and indefinite detention of suspected communist rebels – but kept silent and on the people’s worsening impoverishment and their widespread repressions.”

Yet despite the restoration of the country’s fragile democracy, Nieva lamented that the “liberated media” condemned the late dictator for his “wholesale rape of the country and the communists for persisting in their rebellion — but are silent on the people’s worsening impoverishment and the continuing militarization and repression in the countryside.”

We can only agree with Nieva, considering the effects of these two political episodes on the Philippine press. The problems continue to haunt the media and the industry.

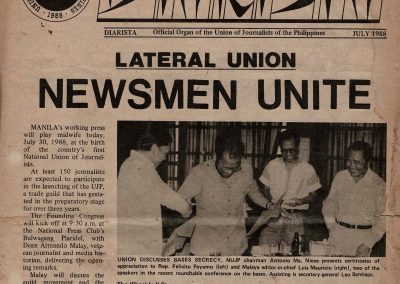

In 1988, as chair of the newly-founded National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), Nieva already forewarned media colleagues that while there was merit in proposals to disperse media ownership, genuine reforms were not held likely to materialize in the immediate future.

“Within the context of national realities, media do not serve to strengthen the Gross National Product any, but they do mold public opinion, however artificial it is, whether the opinion weights for any particular group of interest would largely depend on whose service media are utilized for. In a bourgeois press, as any populist would point out, any opinion cannot but be hostile to the working class,” he said during a tripartite conference on labor and mass media.

The challenge, he said, was for the “seeds of change” through collective organizing works in the ranks of media.

The need to unionize

As a working journalist, Nieva gained the respect of colleagues for his exemplary reportage of the harsh political realities then, while fighting for the media workers’ rights.

Oftentimes, he engaged corporate management in running battles for their right to unionize and bargain collectively.

In 1983, Nieva was arrested and detained for leading the formation of a broad alliance of media unions, a move that alarmed not only the publishers but also the regime. After leading the founding of the Brotherhood of Unions in Media of the Philippines, or BUMP, he was arrested and BUMP was declared an “illegal” organization.

But the struggling unions were not easily cowed. The media workers continue to organize. They were emboldened since those leading the struggle against exploitative business operations were working journalists, disproving the myth that journalists were a privileged class in the industry.

Some of the threatened media owners eventually encouraged the formation of guilds designed for professional advancement, but not for collective bargaining.

Nieva, however, continued to remind colleagues that unionism had always been a part of the wider struggle in the labor movement. The late journalists Amado Hernandez and Cipriano Cid, who were behind the formation of the Philippine Newsmen’s Guild, were leading figures of the Congress of Labor Organizations and Cid was elected its first president.

The state’s answer to the growing militancy of the CLO was a “strong fist” policy during the first quarter of 1951 with the military crackdown on the CLO and the arrest of Ka Amado, who had been at the helm of the CLO since 1947.

With the CLO disbandment, the collapse of the newsmen’s guild was imminent. The first attempt by media practitioners to advance their rights and welfare failed.

What emerged later was the National Press Club, a professional association of newsmen with the backing of the publishers.

Militancy in media

Militancy continued to characterize organized labor in the media. When martial law was declared in 1972, Philippine Herald workers were manning their picket line near Intramuros.

Nieva later recalled that manning the Herald picket line was also his transformation as a media activist, after being an advocate of Bertrand Russell and his peace movement since his college days at the Ateneo de Zamboanga.

After the 1986 People Power Revolution, the competition among media companies became so fierce that the mortality rate increased. A feeling of job insecurity pervaded media workers as newspapers collapsed one after the other in a crowded market.

In the print and broadsheet industry, only unionized workers were able to bargain with management to uplift their wages and get additional benefits.

Indeed, media workers had learned their lesson. We tried to revive the BUMP, but Nieva said that it was also time that media workers become “more organized” and start working towards the formation of an independent labor federation.

In the process, working newsmen started working towards the formation of a union of journalists, independent of the powers-that-be. The National Press Club, he said, will always remain a “social club” because it was controlled by media owners.

Despite the emergence of the Philippine Press Institute led by Joaquin “Chino” Roces as publisher of the revived Manila Times, and Alfredo Navarro Salanga’s People’s Movement for Press Freedom, there will always be a threat to a free press.

It was time, he said, that a union specifically focused on the plight of working journalists, which would include freelance journalists and those working in non-unionized companies.

Nieva led the preparatory committee as interim chair in the formation of the Union of Journalists of the Philippines, while the media unions prepared for the registration of the first media workers’ federation.

While media institutions were mostly Metro Manila-based, the committee was tasked to organize the ranks of provincial journalists who continued to suffer from political harassment after accounting for the most media fatalities under Martial Law.

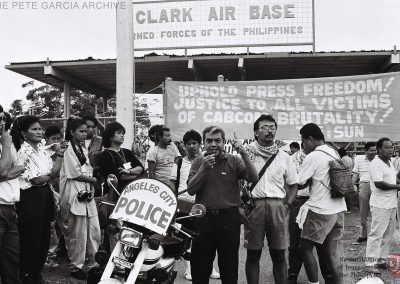

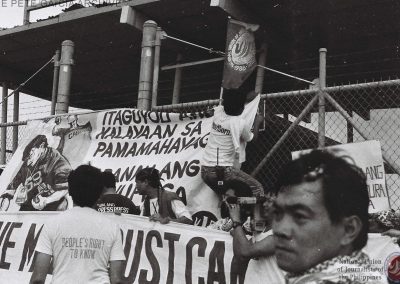

Finally, on May 1, 1987, leaders of the 10 media unions convened in Quezon City to commemorate Labor Day by signing a statement of unity, along with independent groups of journalists who had been part of the interim UJP.

The short-lived Kapisanan ng mga Manggagawa sa Media ng Pilipinas (KAMMPI) was officially founded to protect their rights and promote their welfare.

A resolution was also passed, organizing the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), with Nieva as chair and Leo Santiago, who led the secretariat of the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster sa Pilipinas (KBP), as secretary-general.

Initially, the NUJP worked as a professional newsmen’s guild to help colleagues in need while working to uphold press freedom in and out of the workplace. The goal was to help empower its members to collectively negotiate with employers and government, patterned after the unions affiliated with the International Organization of Journalists and the International Federation of Journalists.

It was then that the NUJP came out with the slogan: “Are you overworked and underpaid? Join the Union.” When another wave of killings of journalists sparked under the new dispensation, the NUJP led the campaign “Don’t Shoot Journalists.”

The press may not actually be free from exploitative and tyrannical control, but the NUJP finally emerged as a balance as the vanguard of working journalists and in defense of press freedom.

Joel C. Paredes is a founding member of NUJP

More from Diarista 2021

NUJP’s comments on proposals for a Media Workers’ Welfare Act

Submitted to the Senate Committees on Labor, Employment and Human Resources Development and on Public Information and Mass Media -- The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines welcomes...

Layoffs loom at state broadcaster Radyo Pilipinas

Layoffs at the Presidential Broadcasting Service, which operates Radyo Pilipinas, will affect at least 10 Contract of Service staff, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines has learned....

Fight for justice for Ampatuan Massacre victims continue, kin says

The pursuit for justice for victims of the 2009 Ampatuan Massacre is far from over, three years after several of the accused including members of the Ampatuan clan were convicted for multiple counts...