The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines held its first congress 33 years ago today as a guild for journalists working in a fragile democracy.

It was a product of years of organizing that started during the Martial Law years, when union work as well as journalism itself was fraught with danger.

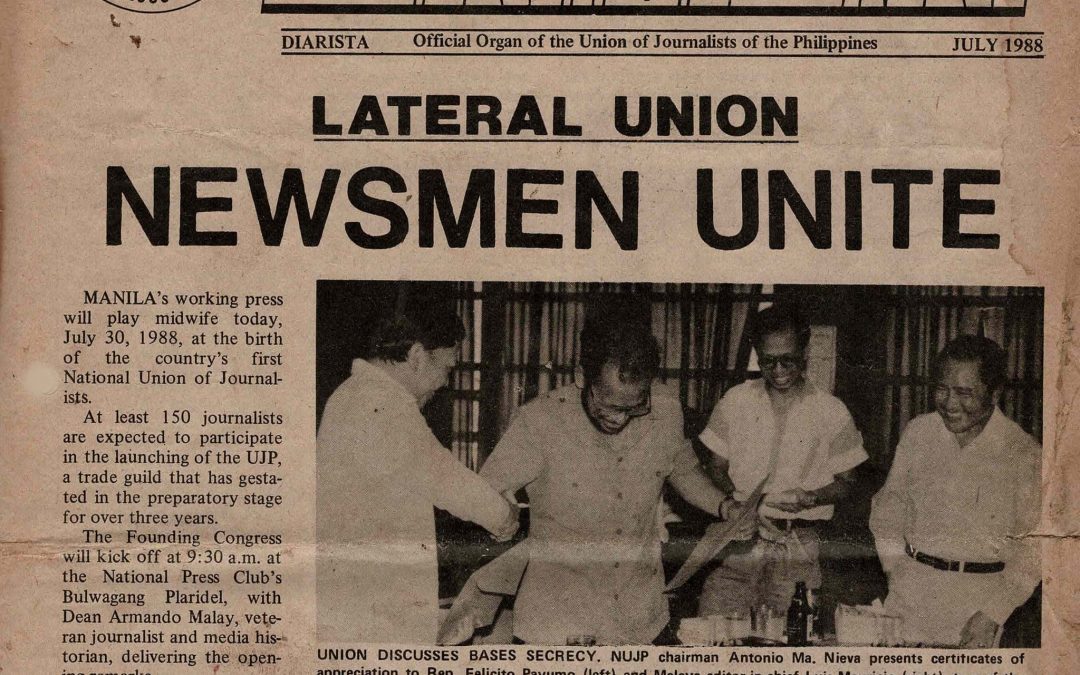

Unionist and journalist Antonio Ma. Nieva — NUJP’s first chairperson — was, according to union founding member Joel Paredes, considered dangerous back then for supposedly being a communist and for criticizing the conservative Philippine press at the time.

Nieva, who was arrested and detained in 1983 for leading the formation of a broad alliance of media unions, said then that “the controlled media wrote reams of copy in praise of the regime, justifying ‘salvaging,’ the militarization of the countryside and indefinite detention of suspected communist rebels – but kept silent on the people’s worsening impoverishment and their widespread repressions.”

Although democracy was restored in 1986, the media remained, he said, “silent on the people’s worsening impoverishment and the continuing militarization and repression in the countryside.”

It was in this context and while media workers labored for low pay and paltry benefits that Nieva and other progressive journalists worked towards forming “a union specifically focused on the plight of working journalists, which would include freelance journalists and those working in non-unionized companies.”

The state of media more than three decades later is not far removed from the days of Nieva and the first members of the NUJP.

The tendency to label journalists as terrorists, communists or enemies of the state is also back while the government has not held back on using legal and regulatory processes as well as economic pressure to further control the press.

Colleagues have been arrested and charged, newsrooms have had their operations threatened simply for doing their jobs. We have also documented incidents of surveillance on and intimidation of journalists during the pandemic lockdowns.

Twenty have been killed since 2016 and many who have not been targeted by attacks are in dire straits as well.

An NUJP survey of media workers earlier this year found that 44% receive a monthly salary of P15,000 and below. Fifteen percent are paid P5,000 and below each month and 70% said they have to take on other jobs or have small businesses to augment their income.

Half of the respondents said they are not entitled to holiday pay, hazard pay or insurance. Fifty-five percent said they are not given overtime pay.

Nearly 40% do not have a health card and 35% had to provide their own personal protective equipment while covering the largest health crisis in recent history.

In a separate survey by the Photojournalists’ Center of the Philippines (PCP), 27% of respondents said they get P30,000 per year or only P2,500 monthly for their work. Of 75% of respondents who said they were paid per photo used, 17% percent are paid less than P300 each. In some areas, photos go for as low as P75.

Many in the media have also had to make their own arrangements for COVID-19 vaccines despite being labelled and sometimes hailed as essential workers.

NUJP began as a professional media workers’ guild for the mutual aid of media workers’ and to uphold press freedom. It was also created to empower its members to organize and collectively negotiate with employers and with the government.

The press freedom situation in the past five years has shown us that there is as much a need now as there was 33 years ago for media to organize to defend press freedom, protect each other and advance not just our professional skills but our power as a sector as well.

The union’s slogans in the late 1980s, like the call to stop the killings of journalists, are as relevant as they are now.

One we would like to revive on our 33rd year and in the face of economic pressures that journalists face is this one: “Are you overworked and underpaid? Join the Union.”